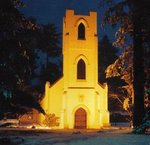

On November 1, we had a guest preacher at St. James'. Luanne Panarotti, an aspirant to the ministry in the Presbyterian Church, preached on the raising of Lazarus.

My name is Luanne, and I am a weeper. I come by it honestly, perhaps genetically; my mother was a weeper, too. She was, in all other ways, a pretty feisty bird; but, she had a sentimental streak that ran deep and wide, and that caused her to well up at some of the most unusual things.

I can remember an evening long ago, sitting in our living room, watching the Miss America Pageant. I was curled up in the armchair, my mother was on the couch, and Bert Parks was singing, as the winning beauty, be-sashed and tiara-ed, began her tearful teeter down the runway. I looked over at my mother and saw her – face puffy, lips quivering, eyes brimming over – trying to hide behind a throw pillow, and I thought, “What on earth is the matter with her?” Now, some forty years later, I cry over happy movies, old songs, Hallmark commercials, Project Runway dismissals, mailings from colleges, every time I watch Cedric Diggory die in Harry Potter IV, bunny rabbits, tiny shoes, certain shades of pink – well, you get the idea: it doesn't take much.

Jesus was not a weeper. He was often deeply moved. He was sometimes greatly troubled. He, on occasion, cried out. But he rarely wept. In fact, Jesus weeps on only two occasions in the gospels. In the 19th chapter of Luke, upon his triumphant arrival at Jerusalem, Jesus weeps over the city that would welcome him that day, and turn on him the next. He weeps again in today's passage from the gospel of John, the well-known story of the resurrection of Lazarus. In the King James Version and other translations, it is the shortest verse in the bible – just two words, “Jesus wept.” – and yet it is so incredibly laden with meaning.

For one thing, it makes a potent theological point. This gospel was most likely written at the end of the first century, when the whole notion of Christianity was still in a state of definition and flux. There were heresies afoot, unorthodox ways of thinking that threatened to tear apart the fledgling community of Christ; one such doctrine, was Docetism. Now, Docetists believed in Jesus' divinity, but not necessarily in his humanity. They thought that spirit was good and matter was bad, and it wasn't particularly becoming for God to get all tangled up in the messiness of the flesh. They suggested that perhaps Jesus only seemed to have a real human body, but was more of a phantom; that his suffering and his crucifixion were merely appearance. Needless to say, this way of thinking undermined the idea of Christ's physical sacrifice on our behalf, and the ability of fleshy humanity to share in his resurrection. So, this simple statement – Jesus wept – is really quite profound. Through it, the author of the gospel is saying no, Jesus was a real man; he ate and drank and shed real blood – and see, he cried real tears.

But I can't help but wonder, why cry now? Jesus certainly had ample opportunity for sadness and frustration in his lifetime. Starving in the desert. Misunderstood and rejected by his own people. Tortured. More than enough to bring any of us to our knees, let alone to tears. Why cry now, over a man he knew he was about to bring back to life?

Compassion is often given as the answer: Jesus wept at the sight of the others mourning. Of course, it's our understanding that Jesus was regularly faced with a procession of lepers, paralytics, the blind, the possessed, the sick, the dying; surely he would have been moved to tears by their plight, but the gospels never state that he lost his composure. Other Bible commentators suggest that Jesus wept from sorrow over the lack of belief of those closest to him: even his friends and followers didn't appreciate the full extent of his power, didn't believe that he could raise Lazarus from the dead. Well, if that were the case, Jesus would have been weeping all the time because he was rarely appreciated for whom he really was, by anyone – friends, family, religious leaders, the entire Hebrew people who had been waiting for him for generations. In fact, the only ones who seem to consistently recognize Jesus in the gospels were the demons he cast out of the possessed.

So it seems Jesus did not weep over his own hunger, his lack of social stature, the fact that he was so misunderstood. He did not weep at his own physical suffering, nor even at that of those around him – though in his compassion he did heal them. What is it then that moved him in this instance? What does this passage tell us about what makes Jesus tick?

I think it says something about what Jesus values – and it's not personal comfort or gain or notoriety, all the things that usually define success in our society. No, above all, Jesus values relationship. He was built for it. It was knit into his bones when he was made man, and it infused his very soul as a member of the blessed Trinity. He comes from community, he is community: relationship is what makes him complete. And he left that heavenly love-fest to invite us to join it, to seek that same completion in communion with God, and to do it in communion with one another. So when we do not, like Jerusalem turning her back on relationship with Christ, and when we cannot, because death has come between us and those we love, Jesus weeps. For our loss, and for his.

So, what can we discern from this passage, for our own lives? The first thing that comes to mind is that it tells us something about how to be in relationship with those who are mourning. Humans are so uncomfortable with death; we often don't know what to do or what to say in the face of it. Unfortunately, I think our Christianity can even get in the way of our humanity when dealing with those who are mourning. Sometimes in our effort to affirm our belief in the life to come, we can find ourselves diminishing the significance of lives lived here.

We try to comfort the bereaved by saying things like “He's in heaven now”, “She's in a better place” or my favorite, the one someone recently told friends of mine who were mourning a miscarriage, “God knew that the baby would not be viable, so it's a blessing that He took him.” Those things may all be true, and those of us who believe in the promises made to us by Christ can live in hope that our stories will end well. But, if this passage about Jesus weeping over Lazarus tells us anything, it is that we must also allow the experience of grief. It is part of our human existence, to feel pain when relationships are severed, not something to be ashamed of or gotten over because it makes those around us uncomfortable. There is blessedness and purpose in mourning.

I had the opportunity to interview for the Clinical Pastoral Education program at Vassar Brothers Medical Center, a training program for hospital chaplains. The supervisor of the program, a Buddhist, posed a scenario for discussion: you are meeting with a family that has just lost a child, and they ask you “Why would God do this to us?”. I admit, my first inclination was to rush to God's defense: “These unthinkable tragedies of life are not visited upon us by God. God is there to offer strength and solace when we are facing such unimaginable pain, he mourns with us.” And she said to me “You can't answer their question; you're not there to provide answers. You are there just to be with them for a while, and hold their screams.” When you find yourself faced with someone in mourning, resist the impulse to defend God, or to offer platitudes. You may wish to share your most heartfelt belief in Christ's promise to us in the resurrection, but in the end, just be with them, and perhaps weep with them, as Jesus did with Martha and Mary.

After Jesus wept, he brought Lazarus back to life. Perhaps, on this All Saints Day, we might also consider following Christ's example in doing some resurrecting. Now, as much as we might yearn to, we cannot bring back those who have gone on to eternity before us; if that were the case, I would have my mother back on that couch in an instant, even if I did have to watch the Miss America pageant again. No, we need to leave those saints to enjoy their heavenly feast, until we can join them there.

But perhaps there are relationships that were once a part of our lives, that have died an untimely death. Marriages that have wasted away due to neglect or malnourishment. Family bonds broken by the sickness of addiction. Friendships that were dealt a death blow by deceit or greed or jealousy. Maybe it has been so long that you can't even remember the cause of death, yet you still are mourning the loss. Is it possible for you to try and push away that stone? Can you stand before that tomb and call out to that once-beloved one and try to bring them into relationship with you once again? Do you have the courage to unwrap the cloths of denial and anger and mistrust that have hidden the face of that one from your clear view? I'm not saying it is an easy thing to do, or even always possible; if that relationship has been mouldering for a while, there may be quite a stench to get past.

But we have been called by Christ to imitate and participate in the loving community of heaven, and for now, this is the stage upon which we do it.

On All Saints Day, we remember and celebrate those who have gone before us, and look forward to the time when, as the author of Revelation writes, “God will be with us, and he will wipe every tear from our eyes. Death will be no more; mourning and crying and pain will be no more.” Until then, let us seek relationship with one another, and with Christ. Anything less would be a crying shame.